Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell North High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

A Tear in the Daily Life

Published: April 3, 2019

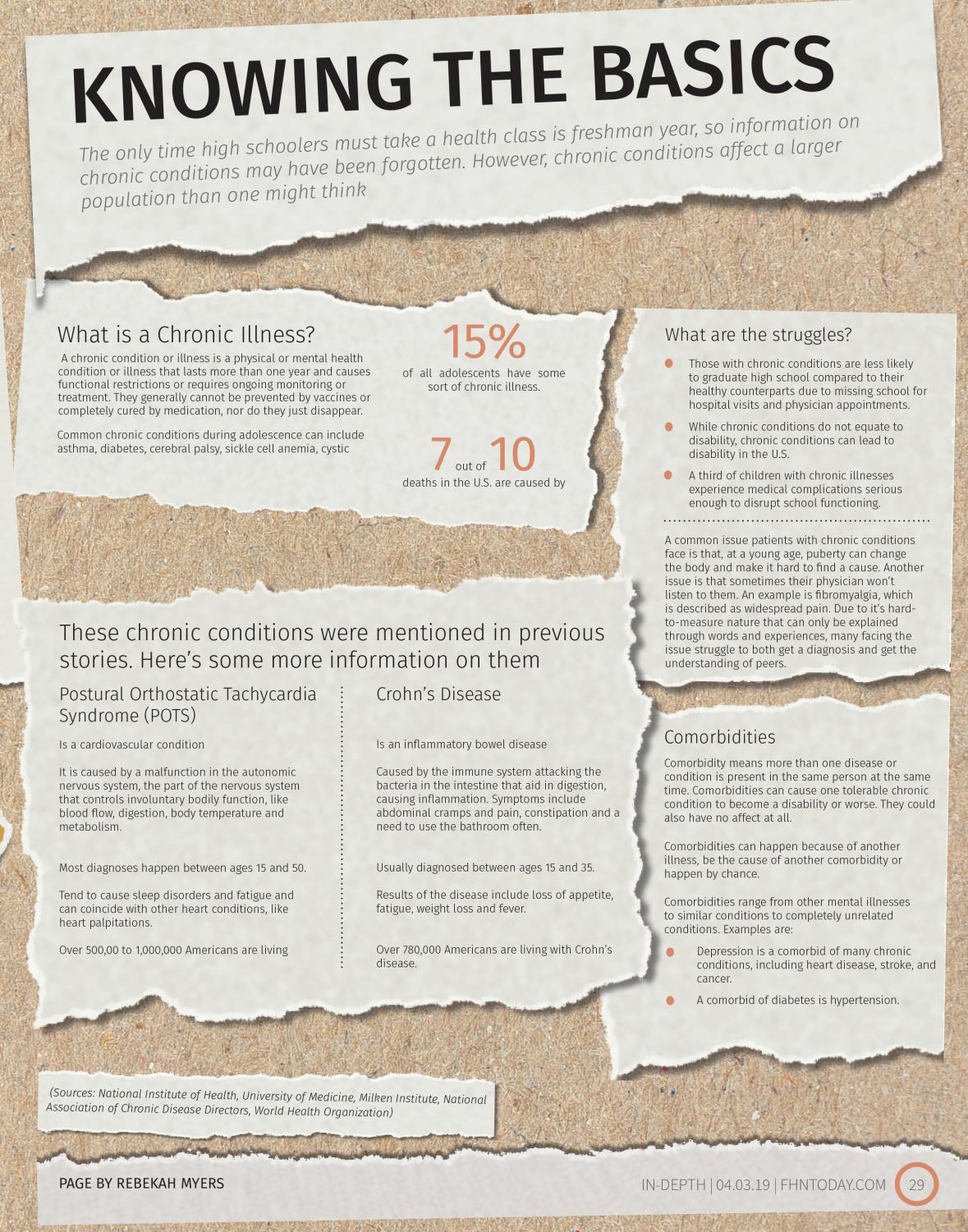

For adolescents, feeling exhausted tends to be an expected norm. This, with other changes in the body happening at this time, tends to make the body act in strange and abnormal ways. This leads to bigger, more impactful abnormalities blending in, causing those with real, life-affecting conditions to struggle to find what they are truly afflicted by. (Design by Rebekah Myers; Photos by Francisco Jiminez)

Credit to Francisco Jiminez

Chronic Illness, Chronic Disruption

After a restless night of getting up to use the restroom, sophomore Marcus Otto knows it’s going to be a bad day. He’s experiencing severe stomach cramps, vomiting, trips to the bathroom and the inability to eat. These days can vary in occurrence, from twice a month to a consecutive week. Having gone through a bad day like this before, Otto realizes he has to stay home from school.

Otto has Crohn’s disease, a chronic illness which affects the lining of the digestive tract. The immune system views the bacteria in the stomach and lining of the intestines as foreign and can cause a multitude of symptoms, including cramps, pain in the abdomen, bloating or nausea. Otto was first diagnosed when he was in seventh grade, when stomach pain and muscle aches drove him to seeing a doctor. After 12 months, three doctors visits, multiple tests and a cancer scare, a gastroenterologist determined that he had Crohn’s disease.

“I was happy that it wasn’t cancer at first,” Otto said. “When I started doing research, I realized that there is no cure and that it’s never going to go away. So, that kind of bummed me out. You know, you get the medicine to treat it and it treats it fairly well, but it’s going to be there forever and it’s never going to go away.”

Chronic illness is a disease or illness that is recurring or permanent. Examples of chronic illnesses include cerebral palsy, autoimmune disorders, cancer, epilepsy and obesity. There are also a variety of developmental and learning disorders, like ADHD and bipolar disorder, that are considered chronic illnesses. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, almost one in three adolescents ages 12 to 17 had at least one chronic health condition in 2011 to 2012. These conditions could potentially affect their schoolwork.

“It could impact attendance, of course, if they need care within the school day,” counselor Lisa Woodrum said. “Even if they’re maintaining [their health] a little bit and they can do school, oftentimes those appointments would be during the school day. For a chronic illness, the impact on learning can be significant based on the coping skills of a person. We know that, whether you’re an adult or a teenager, if you have a really nice support system, you might be able to handle more. But sometimes, if people don’t have a support system, or maybe their coping skills don’t match their chronic illness, then we know that the learning new concepts, application of those concepts, we know that there could be a delay [in learning].”

Not only is attendance and grades impacted, but social interaction between peers could be at risk. When Otto was first diagnosed, he was missing a lot of school, therefore impacting his attendance, grades and interaction with others. There are many necessary advantages to teenage socialization, including a sense of belonging, a way to experiment with new ideas and values and a feeling of being valued, which helps with confidence. If a student is absent due to chronic illness, they could be missing out on these important steps in socialization.

“If a student is not able to be at school full time, that would be really hard and it is hard for those people, especially when you’re supposed to be social and young and learning all kinds of information and skills about peer relations,” Woodrum said. “It does have a negative impact [on their social life] sometimes and on their learning, because as humans we are social beings. So, if you don’t have somebody to talk about that science concept with or kind of commiserate and say ‘I really did not understand what they wanted on this essay,’ then that definitely not only affects their health, but it also impacts their ability to learn.”

The percentage of chronic illnesses in children is steadily increasing, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, although it is unclear if it is due to an increase in the prevalence of chronic illnesses, improvements of diagnostic criteria or a combination of both. Schools are having to figure out solutions to help the kids affected by these illnesses. One solution at FHN is a master pass, written by the school nurse and excuses the student from any class if they need to see the nurse, use the bathroom or for any other reason pertaining to their illness. Another solution is the Homebound academic plan for students who cannot physically come to school. Homebound instructors visit with the students for five hours a week either at home or a library to give the student their work and offer any help. There are different variations of this plan where some can come in for a partial day, depending on what works best for them and their illness.

“The schools are trying to be as accommodating as they can so the person can have the most out of the education,” school nurse Brooke Magilligan said. “We try to help give supports to help them because they can’t help the fact that they have this chronic illness.”

Dealing with Dysautonomia

In the heat of July, senior Sydney Wise feels a panic rush over her as she sits on the ground near the practice field for marching band. A few moments prior to her break, she felt a dizzy sensation, but it didn’t happen just that day, it continued to happen for three days before she decided to see a doctor.

“In the beginning was when I felt the most panicked,” Sydney said. “I really only thought it was because I was dehydrated. It freaked me out that I had to sit out everyday. I got in my head about the situation.”

Sydney ended up seeing a cardiologist and they performed an ultrasound on her heart and an EKG, or electrocardiography, which is the process of recording the electrical activity of the heart. They told her that she has a chronic dysfunction in the automatic nervous system called dysautonomia, which is a form from an illness that her dad Kent Wise also suffers from called Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), which is when someone stands up and their blood pressure drops so their heart rate speeds up. One of the main issues with it is an increase in dizziness.

“Seeing what my dad goes through every day and the thought of what he has to deal with, I just don’t want to go through that,” Sydney said. “I know how much pain he’s in and I know how frustrating it is to not be able to do the things you want to do.”

Kent also carries a chronic illness called Ehler’s-Danlos syndrome, which is a syndrome where connective tissues are missing from joints and muscles. This specifically causes Kent a lot of pain in his torso. Sydney has a 50 percent possibility of carrying as well. She won’t know exactly what she carries until she visits a geneticist. She plans on seeing one later this year.

“I think because I was very physical and being involved in sports, I didn’t notice things,” Kent said. “It took a lot longer for my condition to settle in. Sydney is showing beginning signs.”

Sydney and Kent’s conditions aren’t only affecting them, but it also affects their family and especially Kent’s wife Jen Wise.

“It’s not easy watching this situation go down, and it’s definitely a little stressful,” Jen said. “I’m not the one experiencing dizziness or pain, so it’s totally different for them. I have to redo and rethink a lot of how I do things. The amount of things I have to do is far greater than it used to be. It’s made me have to change things about myself like things I have to give up because I have to take care of things I normally don’t have to. I’m not saying that’s necessarily a bad thing because I’ve found joy [with my children and normal housework].”

For now, Sydney has to drink a around a gallon of water and exercise for 30 minutes a day to help with the dizziness. According to Sydney, some days are better than others, which goes the same for Kent.

“It can be frustrating because I’ll be wanting to do something as simple as driving, but I can’t because I’ll be too dizzy,” Sydney said. “Sometimes I’ll have to miss school. Drinking water helps but there are some days I’ll have to take extra care of myself.”

Credit to Francisco Jiminez

A Foggy Future

He doesn’t know exactly what’s wrong. His heart occasionally skips a beat, or beats once too many or beats abnormally fast for periods of time. The failure of his heart to regulate itself gives freshman Mekhi Brooks’ chest and limb pain, dizziness, tunnel vision and serious fatigue. This isn’t always clear, as the symptoms come in waves, so at one point in the week, Mekhi could be functioning well, while in another time of the week, he would seriously struggle to stay awake in class or even comprehend the lesson being taught. He is affected not only during school, too, as he faces the same symptoms at home, making it hard to catch up on homework he didn’t get finished during class.

“It’s kind of frustrating, because I will try to do my work and everything, but it’ll either just come out bad, or I just flat out can’t do it,” Mekhi said. “But then, I don’t want to use [my condition] as an excuse. But then, I just can’t get anything done. So, it’s frustrating.”

For now, there is nothing to help Mekhi keep up with his work, either, as he is currently not diagnosed, therefore not being treated. This condition first began affecting Mekhi in the seventh grade, yet there has not been a solution. According to the Brooks family, at his age, doctors are holding off on diagnoses, as they do not know what is causing his episodes and do not know if it will fix itself over time as Mekhi finishes growing. For all the that the doctors know, it could be anything from a dietary issue, to an overactive heart, to a nervous system issue. Another issue is that since he was in a better wave of health than usual during the last time his heart was monitored, the doctors assumed that he had miraculously healed, despite them knowing that he still faces these symptoms. Because of this, Mekhi has not been given any treatment, medication, or direction.

“It’s very frustrating because when he doesn’t have a diagnosis, there’s nothing we can do for him at this point,” Mekhi’s mother Sarah Brooks said. “They just said that it’s a common thing for teenage boys to have these problems when they’re taller and lean, that they can have issues with blood pressure and things along those lines. But his blood pressure’s been fine. We’ve been monitoring it at home and it’s been fine. So I think, all in all, they really don’t know what it is, but it is definitely something that affects him in his day to day life. Then people tend to disregard it sometimes because ‘Well, you don’t have a diagnosis with it, so, you’re fine.’”

Mekhi participates in drama, choir and FHN’s swim team. However, there are some stressors that put these activities at risk. Continuing to do extensive physical activity leaves Mekhi with the possibility of fainting. The fatigue can restrict attendance and grades as well, which may close some opportunities in those extracurriculars. However, with proper treatment, which could possibly include medication, a high-salt diet and therapy, Mekhi will able to enjoy these activities again in the possible future.

“I’m hoping that I get a for-sure diagnosis [after future appointments] and that they have a treatment so that I can get better and start getting on top of my schoolwork again,” Mekhi said. ”I just hope they find a way to make me better so that I can function normally again. But I think as of now, all I can do is wait and it’ll either go away on its own or I’ll be stuck with it.”

Normalcy in an Abnormal Environment

Laughter. The sounds of children socializing as they create artistic masterpieces come from one side of a colorful hallway. Music. The sounds of a young man singing his heart outcomes from the opposite side of the colorful hallway. Light. The light from a rooftop garden comes from the large glass doors. These elements all converge in that one colorful hallway, a place where all worries seem to fade away.

The lights in the Child Life Playroom at St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH) are dimmed to a relaxing level as the children finish an art project. This is just one of the many activities that bring kids and teens laughter during their time at SLCH, and it is run by a special department at the hospital called Child Life Services (CLS). This department, as CLS Supervisor Tyler Robertson puts it, promotes a change in perception on extended stays in a hospital for both the patients and their families.

“It has had a tremendous impact on the way families view hospitalization,” Robertson said. “The child life specialists provide education. They provide coping skills. They provide things that just help to continue a child’s development.”

Among those resources, CLS provides is a school program for children who are missing school because of their illness. The CLS School Program is made up of school teachers who will assist kids in whatever school work they may be missing. They will help to modify study habits if their illness has caused them to need an alternative education plan, and they even help schools determine what might need to be permanently different due to a severe illness. School Program Teacher Linn Casper believes this to be a vital role in patient care due to its commitment to maintaining consistency in the lives of their patients.

“We are a big piece of these patients feeling like a normal and typical kid whose life isn’t going to be set back because of their illness,” Casper said. “It keeps them connected to their real life.”

Keeping kids tied to their normal life is one of the purposes of CLS. Another purpose lies in the various facilities sprinkled throughout the hospital. They have various playrooms for patients of any age, and there is a large teen lounge for teenagers and adolescents who are spending an extended amount of time at the hospital. There is also a rooftop garden for patients and families to enjoy during their time at SLCH. These facilities provide patients and families a chance to escape the medical setting and relax.

“By giving children these coping skills and opportunities to play, we can help minimize the negative stressors that come from being in the hospital,” Robertson said.

Ensuring a sense of normalcy and providing coping skills for long term hospitalization are what CLS focuses their attention on. The ways in which they employ this mission is dependent on the needs of the kid. Regardless of the patient’s medical condition, however, the CLS team dedicates their efforts to ensure the mental, physical, and social development of the patients of SLCH in order to make them feel at ease in a medical setting.

“If you think of a child’s development as a ladder, our team helps them get to that next level, whatever that may be,” Robertson said. “Child Life Specialists really gives these kids a chance to be a part of their care, rather than a recipient of it.”