CTE Disease Takes A Toll on Players

Credit to Wil Skaggs and Alex Rowe

Published: December 15, 2017

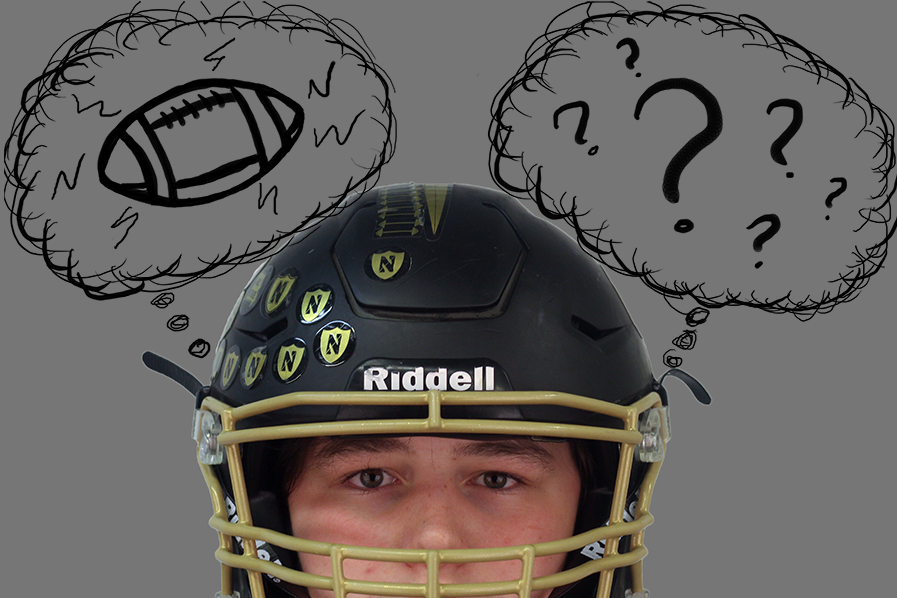

To a football player, a crack can be harmful to hear on the field. A crack in the leg is at least a torn hamstring. A crack in the arm is usually a broken bone. A crack in the chest is more than likely a broken rib. The crack of two helmets clashing is quite common but can lead to injury for the players. Although it may get a crowd going, the effects of each individual hit can leave a lifelong impact on players.

A neurodegenerative disease has recently taken a prominent role in sports discussions around the world. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is described by the Concussion Legacy Foundation as a disease that degrades the brain. It is very common among those that suffer repeated head trauma, including athletes who make a lot of head contact, such as football, hockey and soccer players and boxers. The disease is caused by a protein called Tau that forms clumps that spread throughout the brain, killing brain cells. As time goes on, the disease will continue to spread and attack the brain.

“It’s worrying me because lately it has been on a rise, in some cases in high school,” junior and varsity football player Dominic Griffero said. “I have a bright future ahead of me, and I don’t want CTE to affect that.”

According to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, victims will start showing symptoms in their late teens to early 30s. The first symptoms displayed are behavioral and mood changes. As the patient ages, they begin to show signs of memory loss, confusion and progressive dementia.

Individuals can also never be certain that they have CTE. Currently, the only way that a patient can be officially diagnosed is by an autopsy. There is no known cure to stop the spread of the protein. The only thing doctors can do to treat the disease is to give the patients medicines to slow the spread and to treat the symptoms individually.

At FHN, athletes in contact sports are required to take an impact test. Impact tests are used to measure an individual’s memory and reaction. After suffering head trauma or a concussion, many athletes will take another impact test. If the results are significantly different, the athlete won’t be cleared to play. Coaches also teach student athletes to change their tackle methods, decreasing the shock their heads receive upon impact.

“We teach to hit with the hard part of our shoulder pads,” head football coach Brett Bevill said. “Where in the past when I was around football, we usually hit with our helmets.”

In late July 2017, JAMA, a medical journalism network, released an article on the source and effects of CTE. The study conducted in the article involved players from all levels: youth, high school, college, semi-pro and pro. Out of the 202 brains tested, 177 (87 percent) showed minor to severe cases of CTE.

“I don’t want to be around something that’ll be completely dangerous to these kids,” Bevill said.

The highest concentration was in NFL players where 110 of 111 (99 percent) brains showed signs of the disease. The article quickly gained traction in the sports world. The NFL was one of the first major sports organizations to react and release a statement on the article.

“The NFL is committed to supporting scientific research into CTE and advancing progress in the prevention and treatment of head injuries,” the NFL reported back in July of this year in response to the JAMA study.

Mississippi State University student researchers are working to make football helmets safer by taking inspiration from nature. The team is taking inspiration from the skulls of longhorn rams and woodpeckers. The team has been able to make a prototype helmet that decreases the odds of concussion rates three fold by making an outer layer of titanium and composite and changing the inner lining. Scientists like these hope to find a way to fight this disease.

![FHN Holds Prom at Old Hickory Country Club [Photo Gallery]](https://FHNtoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Brewer_stopmotion-9-300x200.jpg)

![FHN Boys Varsity Volleyball Team Goes Against Troy [Photo Gallery]](https://FHNtoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_7545-300x200.jpg)

![FHN Students Watch the Solar Eclipse [Photo Gallery]](https://FHNtoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/4.8.24-solar-eclipse_-300x200.jpg)

![Girls Varsity Soccer Takes a Loss to the Timberland Wolves [Photo Gallery]](https://FHNtoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_0237-300x200.jpg)